Being invited to teach at a venue as well-known as the Southbank Centre was not something I thought would happen anytime soon. However, just last weekend, along with one of my art buddies and partners in crime Tasleema Alam, founder of Traditional Ateliers, we were invited to deliver an afternoon of workshops which would form part of the Alchemy festival 2016.

The Alchemy festival is, as on the Southbank website, ‘a vibrant array of performances, workshops and exhibitions – and a delicious food market. The festival celebrates the rich cultural relationship between the UK and the Indian subcontinent, and explores the cultural influences generated by our shared history.’ But which version of that shared history?

Whilst this is all very exciting, and a celebration of any BAME culture especially important, it did lead me to question the content and programming of the festival. Music, theatre, literature, art, fashion and so on, are all important and equally valid, but at the same time, what about our history, heritage, our suffering under a brutal occupation and colonialism, what led to the bloody partition and struggle for independence. And what of the pre-colonial civilisations of the sub-continent, are their advancements in art, architecture and culture to be credited and celebrated. Or was it just a preapproved and palatable handpicked selection of the aspects most colourful and lively, you know, the bits we all like. Pre-packaged to satiate the call for diversity in mainstream spaces.

It also led me to question how important my presence would be in such a space. I was being given the opportunity, one many would love to have, to deliver a workshop on something I love and am passionate about. Something that has been appropriated and even ignored in western art history. How much could I, within an afternoon, decolonise the Alchemy festival. Sounds funny doesn’t it! But it wasn’t just a case of how much, but if it would be possible at all within a space that has an undoubtedly interesting and thought provoking set of events, but is also part of the established art and culture scene of London and the UK.

Mughal designs and block printing as a title was quite self-explanatory. It was an introduction to, and a celebration of the history, heritage, art, architecture and culture of the precolonial India. All in an afternoon! I started off by introducing some images and talking about some of the features most common in Mughal, and therefore Islamic, art and architecture. Focussing on architecture, we discussed the style and embellishment of renowned buildings such as the Jama Mosque in Delhi, Humayun’s Tomb and the Taj Mahal in Agra. Picking out common elements that feature in them all, and are also ubiquitous in Islamic art and architecture across the world, they provided the initial inspiration for the later part of the workshop. We also discussed the symbolic and sacred significance of particular patterns and motifs.

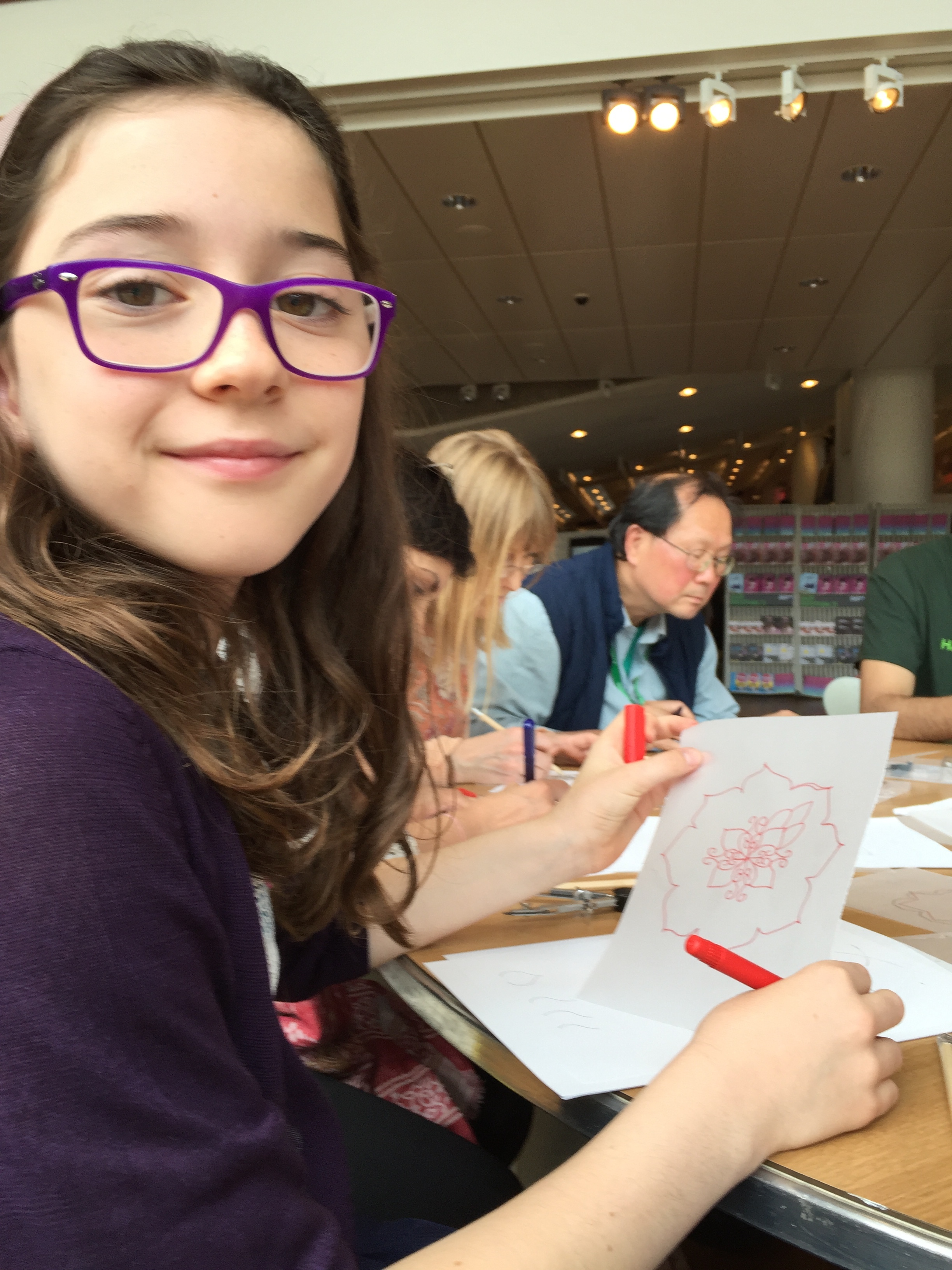

We weren’t sure how many participants to expect, we thought perhaps 10, and were prepared for 15. So delivering to 25-30 with up to 10-15 more people observing was a bit of a surprise, but a pleasant one! Thankfully we had just enough equipment and materials to cover everyone, and following step by step explanations, all the participants drew a perfectly proportional 8 pointed star using just a compass and ruler. This was followed by adding curved lines within the star, which could be inspired by flowers, leaves, natural forms, domes and arches. Each participant created their own individual motif, and it was amazing to see the range of designs deriving from the same principles of geometry and rotational symmetry. Adding colour then took the designs a step further, and enhanced the individual flair and characteristics of each motif.

Some participants were ready to start carving their block prints, which is when Tasleema’s expertise came into effect.

Tasleema introduced the tradition of wood block printing, which originated in China and has been used to decorate and print on fabrics for many centuries. She took us through the process of traditional carving of the wood blocks, and also the dyes used to print on fabrics. Tasleema also took the participants through another method of designing motifs, using the principles of reflectional symmetry, and with her expert guidance and examples, the participants were able to come up with new (or develop their original) motifs in a short space of time.

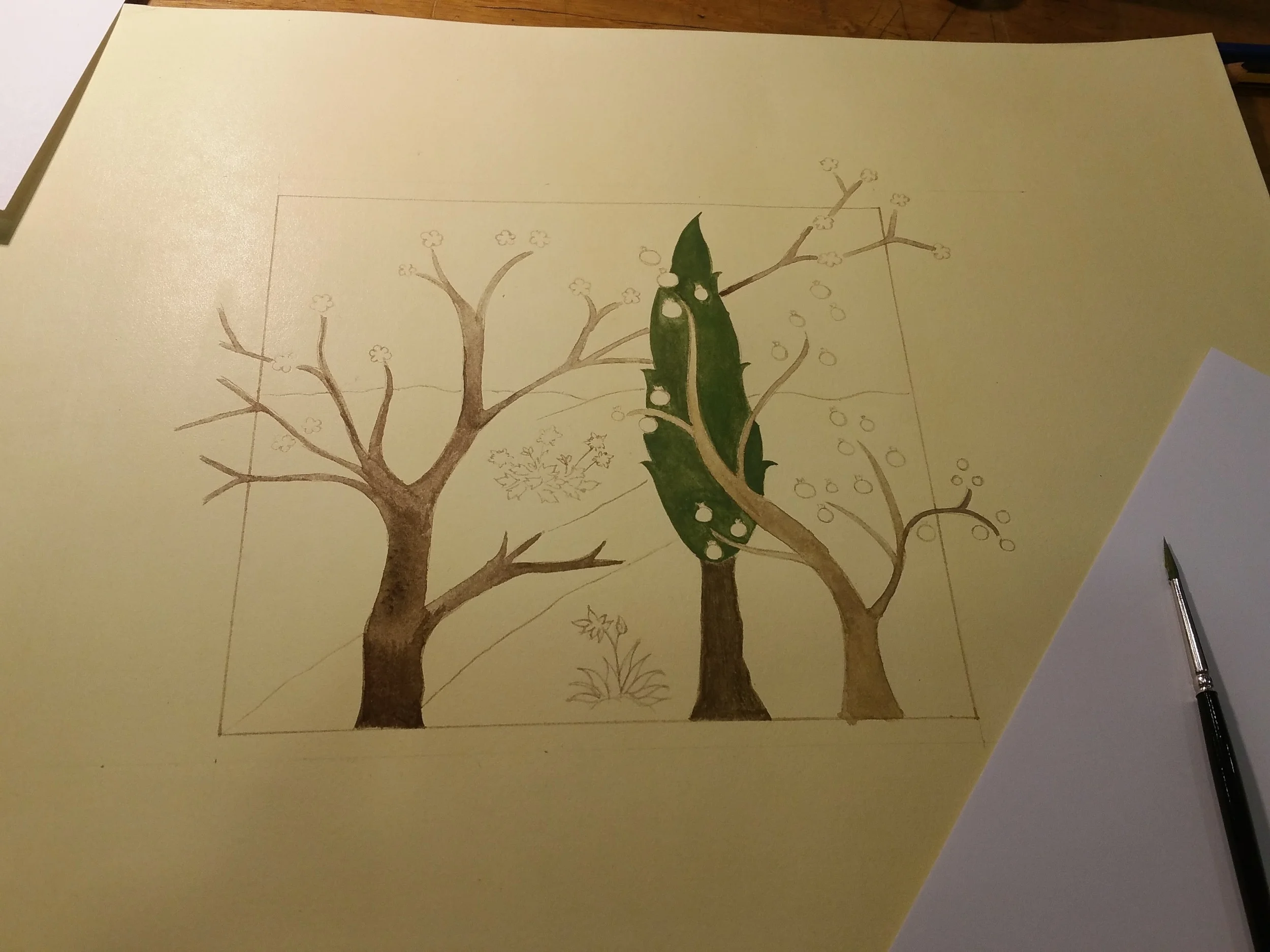

As we were constrained by both time and materials, and in the case of wood carving expertise also, our more contemporary take involved carving small blocks of lino. The participants traced their designs onto the lino, and decided to carve out selections of the design, focusing on positive and negative spaces. Tasleema then demonstrated the printing process, from mixing up the dyes to actually printing. Participants were then able to print using their own carved lino blocks, or use the wide range of hand carved wood blocks that Tasleema brought with her from Bangladesh.

Monochrome and bright and colourful, floral and geometric, rotational and reflectional, inspired by Mughal design and the motifs found in south Asian textiles, the results were fantastic! We received really positive feedback from all of the participants and people observing, and ended up clearing away quite a bit later than planned! None of this would have been possible without the presence of Nyeema Yasin and Shama Kun, who were not only a great help during the workshops, but are also amazing textile artists in their own right.

Nyeema designs the most delicate and beautiful pashminas, which are handmade and hand embroidered in Nepal. Real pashminas which are woven from silk and actual pashmina – mountain goat hair. A rainbow box of colours and hand painted silk ties formed part of a really lovely collection. Shama had with her on display a handmade, hand woven jute dress, which is like nothing I’ve seen before. Beautifully designed and made, it will be on display at the Rich Mix in London soon, so do make sure to check it out.